Embracing risk when we are young

To be risk averse is to prefer preservation over potential reward. On the other hand, seeking risk favours potential rewards over one’s preservation. Each of us falls somewhere on the spectrum between the two.

Human instinct typically places us towards the aversion end of the spectrum. The more we own and are responsible for, the more we want to preserve our status and belongings. We are most tolerant of risk in the early years of our lives. Not only is this because we have fewer responsibilities – but also because our brains have yet to be able to apprehend risk.

As we mature, we slide from seeking risk to avoiding it. We settle down to start families, integrate into communities, and solidify our careers; it’s inevitable that the more we have – the more we seek to protect.

This leads to a period of consolidation that can last for the remainder of our lives. As we reach this stage in life, we begin to live within the confines of what we are comfortable with. We curb the risks we take to preserve what we have.

The extent of our comfort zone depends mainly on our hunger for risk when we are young. The more we push the boundaries while we have less to lose, the more situations and experiences we are comfortable with as we grow older.

If we shirk at uncomfortable situations when we are young, we have no hope of confronting them when we are older. It means we’ll shy from new experiences, run from meeting new people, and avoid exploring new places.

However, we can increasingly stretch our comfort zones if we embrace throwing a little caution to the wind. The more we push, the more people we meet, and the more experiences we have. Both of these are necessary for finding purpose.

These grant us knowledge and wisdom and open more opportunities as we progress through life.

How we anticipate risk

Risk is just another of our brain’s mechanisms to help with decision-making. We calculate risk before every decision we make. It’s present when we cross a road, walk over ice, or invest in a stock. For the vast majority of the time, this is done instinctively. For example, when crossing a road, we rarely have conscious thoughts about the chance of a car colliding with us.

There are other decisions where deliberating risk enters our conscious mind. Investing in stocks is an excellent example of this (especially for the uninitiated). We consider the potential upsides and downsides as we weigh whether to invest. When we take the risk, we accept the potential downsides, hoping for the tantalising upside. When we avert the risk, we conclude that the potential downsides outweigh the potential upside.

Our brain perceives risk in much the same way as anticipating threats (i.e., the fight or flight response). Every day, our brain helps us to make decisions. As soon as we wake, we choose what to wear, eat, and do. Over time, our answers to these become ingrained, and we scarcely even realise there is a choice to make. The more familiar these decisions become, the more our brain hands over control of making these decisions to the instinctive part of our brain.

These choices are familiar because we become comfortable with the potential outcomes (and, therefore, the risks that go with them). For example, when deciding what to wear, we will very often choose an outfit that suits the environment we are going to and the people we will see. We can wear something more provocative, but this would increase the risk of being seen as unprofessional, alienating a client, or simply appearing out of place. Some of us choose the first option because it carries the least risk. Others prefer the second option because they are comfortable with the potential outcomes.

The point I am getting at here is when we make decisions, we all have the option to expose ourselves to more or less risk. The more we expose ourselves to, the more opportunities we become comfortable with. Of course, it also gives us experience of options that are not worth the risk, too – and that only enriches us with greater understanding when making similar decisions.

Suppose we are risk averse and always stick to the safest option. In that case, it means we experience less, explore less, and reduce the number of options we have whenever we are presented with a decision.

Why does taking risks become more challenging as we grow older?

There is no problem with being risk averse – it simply limits our ability to fulfil our potential. When we take the safest option, we close ourselves off from opportunities to take different and more diverse paths in life.

This is most valuable when we are younger, especially before settling down. Not only because this is the phase of our lives when we are most likely to still be discovering ourselves (our values, beliefs, and principles) but also because this is the stage in life when we are carrying the least responsibility. Chances are, we are yet to have children, a mortgage, a spouse, and so on.

As such, the more risks we take at this stage in life, the more familiarity we have, and therefore, the more we are comfortable with within ourselves as we grow older.

Let’s say we are interested in trading. Suppose we spend our years investing in safe bets (index funds, etc.); we become comfortable with a certain level of risk. However, as time progresses, we become increasingly less likely to take high-risk bets that could yield greater rewards.

The reason is that we find security within our comfort. It’s human instinct (as per Maslow’s hierarchy of needs) to choose preservation.

Yet if we were to commit several small, high-risk bets, what we gain is not just potentially monetary; it’s knowledge, understanding, and, most importantly, familiarity with the potential risks that come with bets of that ilk (disclaimer: this is not financial advice).

This concept applies not only to what we wear and invest in; it influences every decision we make. By pushing the boundaries of our comfort zone (within reason), we extend what we feel secure doing.

The greater our comfort zone, the greater the choice and opportunity available later in life.

A little bit of risk leads to a compounding sense of security

Magnus Carlsen is a chess grandmaster and, as of writing, is considered the best chess player on the planet. He spends most of his waking hours playing chess – a game seemingly impossible to master.

In an interview with Charlie Rose, he discusses why being pessimistic and risk-averse holds back many chess players:

“I think it’s always better to be overly confident than pessimistic. I realize sometimes after games that, you know, I was actually way too confident here. I was way too optimistic. But if you’re not optimistic, if you’re not looking for your chances, you’re going to miss. You’re going to miss opportunities. And you know, I think there are — there are plenty of players in history who have been immensely talented, but they’re — they’re just too pessimistic. They see too many dangers that are not there and so on so they cannot perform at a very high level.

In the game of chess, there are more moves possible than there are atoms in the observable universe. So, when a chess player is risk-averse, there are two consequences. First, it limits the number of available moves, as they are likelier to choose a safe option. Second, and as a direct result, they lack an understanding of the seemingly endless number of available moves. In essence, risk aversion limits the number of moves they are comfortable with taking.

While being overly confident and more risk-tolerant will inevitably lead to mistakes, these mistakes enrich the player with a greater understanding of the game and, therefore, more confidence in similar situations.

Meanwhile, Alex Honnold is the first ever to free solo El Capitan (climb without a rope). This feat is far beyond the vast majority of the population’s comfort zone, yet he did it nonetheless. As he mentioned in an interview, “For every hard pitch I’ve soloed, I’ve probably soloed a hundred easy pitches.”

Becoming comfortable with a seemingly extreme level of risk has taken repetition hundreds if not thousands of times at a level he feels secure doing. He goes on to state, “I differentiate between risk and consequence. Sure, falling from this building is a high consequence, but it’s low risk for me.”

I will concede that neither Magnus Carlsen nor Alex Honnold are ordinary cases. Their achievements are extraordinary. But it’s too easy to discount this as resulting from a freak of nature. The method and process of how they get there is something that we can all learn from. It’s a combination of exposure to increasing levels of risk and doing it consistently enough that the level of comfort with those risks gradually increases over time.

How to embrace risk

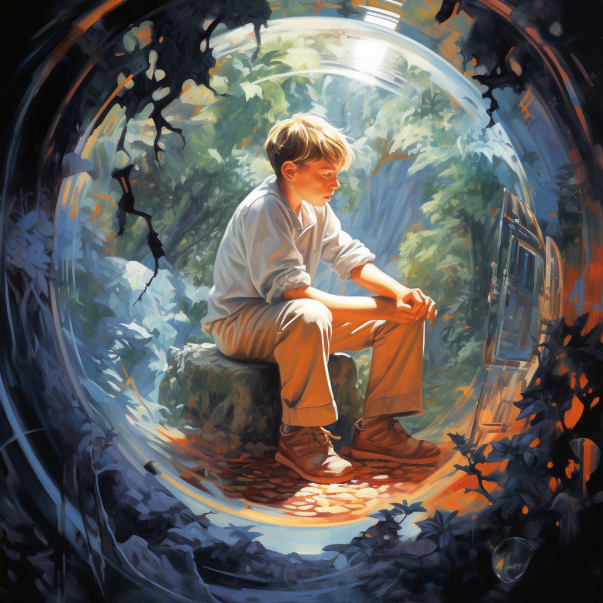

We all have a comfort zone. This emanates around us and within us at all hours. Within this zone, we find warmth, love, and comfort. So naturally, it’s somewhere we wish to exist in. Outside of this zone lies uncertainty, vulnerability and scarcity.

Yet as we have covered, existing outside of this zone is the only way of extending what we are comfortable with. If we have dreams of travelling the world, exploring the oceans or summiting a mountain, we must leave our place of comfort.

To be candid, achieving our dreams means embracing risk no matter how ambitious. Our comfort zones are pliable and can be stretched, pushed, and extended without collapsing in on us.

To embrace risk, it’s naive to think we could leap to doing things we could never imagine ourselves doing. Instead, it’s a marginal daily undertaking, embracing a little more risk today than yesterday. It’s about welcoming the scenarios we frequently shy away from. Daily, how often do you feel regret at not taking action when you wanted to?

To become comfortable with increasing levels of risk, we must accept the discomfort – and even learn to enjoy it. This could be conversations we’ve put off having. It could be actions we hold ourselves back from doing. It could be trying something new every day.

Jia Jiang gives an example of this in his Ted Talk, ‘What I learned from 100 days of rejection‘. Fearing rejection was something Jiang struggled with. This fear prevented him from asking for things he wanted. So, to overcome it, he sought to extend his comfort zone by pushing himself to take a little more risk every day.

By the end of the 100th day, he had significantly increased his familiarity with rejection. That’s not to say that his fear of rejection was cured (our comfort zones only stretch so far) – however, in the space of 100 days, he materially changed the level of risk he was comfortable with.

Embracing risk to reach for our dreams

Our hopes and dreams are so often condemned to our minds. Many of those dreams may feel unattainable, others less so. Either way, to even come close to realising those dreams, it requires taking action.

Doing so will inevitably rip us from where we are comfortable into situations, scenarios, and environments that we are yet to become familiar with.

However, becoming comfortable with discomfort is only possible by embracing more risk daily. While we can expose ourselves to extreme risks, this neglects why we anticipate risk in the first place, and inevitably will only lead to hurt, ruin, or worse.

A little more risk exposure every day has a compounding effect. In 100 days, our bubble of comfort is a little larger. In 365 days, it’s stretched even further. By the time we ready to settle down in the later years of our life, the zone within which we feel warmth, love, and satisfaction is far greater than when we lived a life lingering within it.